Sea turtles spend their lives at sea, only coming onshore to breed yearly or biannually, which is why it was unusual for ORCA Peru to be called about stranded sea turtles. However, when you consider the vast quantities of plastic filling our oceans, it becomes far less surprising.

Plastic is generally made from petroleum and unlike other materials, when in landfills it may never biodegrade. It can however break down in the oceans due to photo-degradation, with UV light rays breaking the molecular bonds and reducing the objects to smaller pieces. With such a large exposure of sunlight in the oceans, plastic items such as bottles or bags can break down in a matter of years, which you may assume is a good thing. However, it is not. Even if the plastics break down into microplastics, they still contain the highly toxic chemicals which end up being ingested by marine life of all kinds. But you shouldn’t be worried just for the sake of the aquatic animals. These toxins end up in fish that is consumed by humans and also chemicals wash up onto beaches giving humans direct contact. Similarly to the aquatic species, we are still unsure of the effects this will have on us in the future.

In 1975 the National Academy of Sciences estimated that around 0.1% of plastic produced a year would end up in the oceans. In 2015, this number more accurately grew to somewhere between 15-40%, meaning that 4-12 million metric tons of plastic washes ashore a year. This problem is much worse though as further scientists have stated that they are unsure of where more than 99% of ocean plastic debris ends up and the quantity is only expected to increase. No one knows the extent of how plastic in the ocean is affecting the full scale of marine life.

As you’ve probably seen or heard, there are several mass accumulations of plastics in the seas with the most well known being the “Great Pacific Garbage Patch”, also known as the North Pacific Gyre. Plastic can travel in currents and accumulate in gyres, which are areas of slow spiralling water with low winds. There are 5 major ocean gyres in the world, but the North Pacific Gyre is approximately the size of Texas with debris also extending 20 feet under into the water column. SEE Turtles has estimated this plastic island contains 3.5 million tons of trash and could potentially double in size in the next 5 years alone.  Photo: Oceanwatch.us

Photo: Oceanwatch.us

The coastal waters of Peru provide a huge foraging area for several sea turtle species – Leatherback turtles, Olive ridleys, Green turtles, Loggerhead and Hawksbill turtles. However, the conservation status of marine turtles in this region is not well documented and many details about the species themselves behaviourally or distributionally are still unknown. For this post I’m focusing on the two species the Green (Chelonia mydas) and the Hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata), due to ORCA Peru’s two latest patients – Ryana and Mariana. Both turtles were emitted as sick and blood test samples and X-rays revealed they were suffering from plastic poisoning. Veterinarian and director of ORCA Peru Dr. Carlos Yaipen-Llanos revealed the two turtles had their intestines filled with plastic which had caused a strong inflammation, disorientating them and causing them to become stranded on the shores unable to eat.

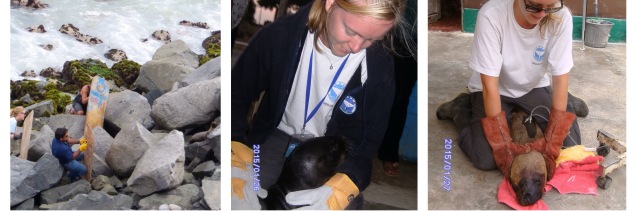

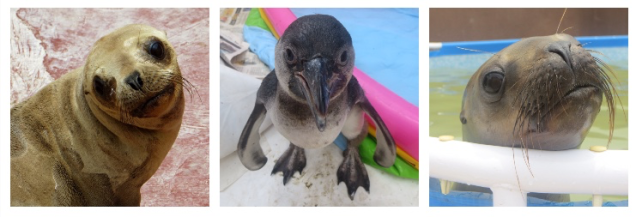

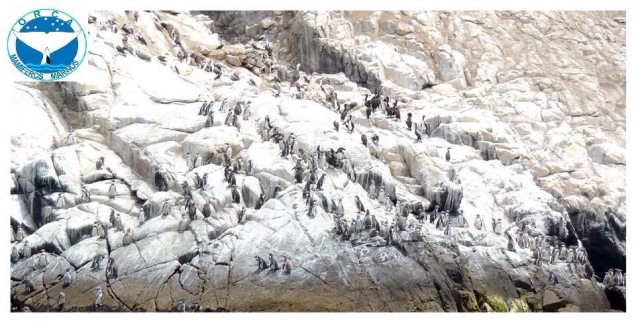

These two species are found in tropical and subtropical waters across the world, with regional groups. Both are suffering from the same problems as other marine animals I’ve posted on here before (sea lions and penguins) – pollution, global warming, nutrient shifts and a reduction in fish stocks, however there are many direct human impacts as well. They suffer from being caught as by-catch in the fish and shellfish industries. Their eggs are also collected for consumption or the illegal wildlife trade industry.  Mariana the Hawksbill turtle and her full stages of rehabilitation.

Mariana the Hawksbill turtle and her full stages of rehabilitation.

Hawksbill turtles also face the threat of becoming a trinket such as a comb or a pair of sunglasses. Their shell is often referred to as “tortoishell” and although illegal under CITES is still used in these trades. It is for these reasons that in 1982 they were listed as Endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species and this was only increased to Critically Endangered in 1996, where they still stand today. This species is actually highly important to the complex ocean habitats where they are found, which in the Eastern Pacific subpopulation ranges from the Baja Peninsula in Mexico to the Southern coast of Peru. The Hawksbills can be found on many coral reefs where they feed off of specific sponge species that would otherwise out-compete many coral, plant and invertebrate species, thus maintaining the biodiversity within these threatened environments. Each Hawksbill female will lay a clutch of eggs of around 140 and many of these will never hatch which actually provides important nutrients to the beaches and dunes on where they’re laid. Mariana the Hawksbill was estimated to be only 15 years old, measuring 64cm and weighing 20kgs. They can reach up to 1 metre and weigh 80kg, although the heaviest one ever recorded had reached 127kg (280lbs)!

Green Sea turtles are listed as Endangered by the IUCN and CITES. They were the first sea turtle species to be studied therefore they are arguably the most studied species of sea turtles. Although that isn’t saying much, their foraging habitats are still not understood fully. The name does not derive from the colour of their shell that can be a variety of colours – it refers to a fatty layer found under the shell that is green. Their range is as far north as Alaska and as far south as Chile, migrating long distances to breed and forage. They can grow up to 1.5m (5ft) and weigh up to a colossal 317kg (700lbs) meaning they are one of the larger sea turtle species and Ryana measuring and weighing in at 48cm and 25kg was a mere juvenile, despite being estimated at 25 years old. The species can live to at least 80 years in the wild, giving Ryana hopefully a long future ahead of her if the quantity of plastic in the ocean is reduced!  Ryana the Green sea turtle being assessed and after rehabilitation tagged and released.

Ryana the Green sea turtle being assessed and after rehabilitation tagged and released.

Both turtles were treated with antibiotics and anti-inflammatory medications and their intestines were pumped in order to rid them of the plastic. After 20 days of rehabilitation from the ORCA staff, interns and volunteers, they had visibly recovered and were released back to the ocean. This was the first time sea turtles in Peru have been rehabilitated and released from plastic poisoning. They were both tagged on their front flippers so if they’re found again they can be monitored.

As a tribute to yesterdays (June 16th) World Sea Turtle Day – deplastify your life! From using as little plastic yourself as possible and not using plastic shopping bags, to pressurising businesses and companies who use unnecessary quantities of plastic, to joining in or starting your own beach cleans there are many ways you can help deplastify yours and others lives as well as your environment. Meanwhile in Peru, ORCA will be continuing their research on sea turtles and rehabilitating any further sea turtles in need. Help the cause by donating at www.orca.org.pe and follow ORCA Peru on social media to get the latest pictures and news of Peru’s vast marine wildlife!